Winter 2025

:

Volume

40

, Number

2

Palestine on Paper

Palestine on Paper

Nestled inside a cardboard box in the archives of a one-room art gallery in Jerusalem’s Old City is a single piece of paper that, for me, succinctly transmits the multifaceted absurdity of the Palestinian experience. The paper is a letter written in March 2004 by Turkish artist Ayşe Erkmen to Jack Persekian, founder of Gallery Anadiel and the Al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in Jerusalem. In it, Erkmen proposes an artwork that would consist of removing an animal from the Qalqilya Zoo in the West Bank “to be exhibited standing next to an animal of its own kind in a natural history museum in Europe for a period of...a month to 6 weeks and then return back to Qalqilya.” By the time of Erkmen’s proposal, Qalqilya Zoo had gained notoriety not only for being the only zoo in the West Bank, but for its gradual transformation from living zoo to natural history museum through events that Erkmen aptly states “are unfortunately sadly funny; Brownie the giraffe dying while fleeing from the sounds of gunfire, falling down and breaking his neck and ten days later his pregnant partner Ruti having a miscarriage because of sorrow and Brownie and his unborn baby giraffe son being stuffed to stand together in a special exhibition space inside the zoo. There is also a stuffed zebra who died of teargas and a stuffed lion among other animals. The owner and founder Sami Khader is doing the taxidermation himself.” Reading Erkmen’s proposal in the archives in 2013, I burst into laughter followed by heavy tears. The tragicomic fate of Qalqilya’s zoo animals—suffering the same trauma and losses experienced by Palestinian people living under Israeli occupation—seemed more at home in the realm of fiction than reality. And, as unbelievably heartbreaking as the stories Erkmen shared were, the gut punch came in the letter’s final sentence: “the more difficult (hopefully possible) part is of course to get these animals out of the borders there.” Like their human counterparts, these animals could move only according to the strictures of the occupation—even as art, even in death.

Owing to Israeli-imposed seizures and curfews in Qalqilya during the Second Intifada, the animals never left Qalqilya in 2004; the artwork was indefinitely “postponed”; Erkmen’s vision remains stuck on paper. I’ve often wondered: does this paper now constitute the artwork? Is the paper a trace or residue of something that, despite its lack of physical realization, exists in the minds of those who have taken the time to imagine it? Or, is the paper the coffin in which the artwork has been laid to rest? Erkmen’s proposal registers to me as part of a canon of artworks whose circumstances of non-realization say as much about life in Palestine as the idea for the artwork itself. Having previously understood paper as a safe space for the preservation of ideas and histories, confronting this paper in the archive provoked a reconsideration: In what conditions—and for whom—is paper a place for safekeeping and a place of potential, of imagination outside the confines of reality? And in what conditions—and for whom—is paper a place of forgetting and of the forgotten? When is paper a symptom of oppression? Which parts of Palestine have been preserved on paper and which parts have not?

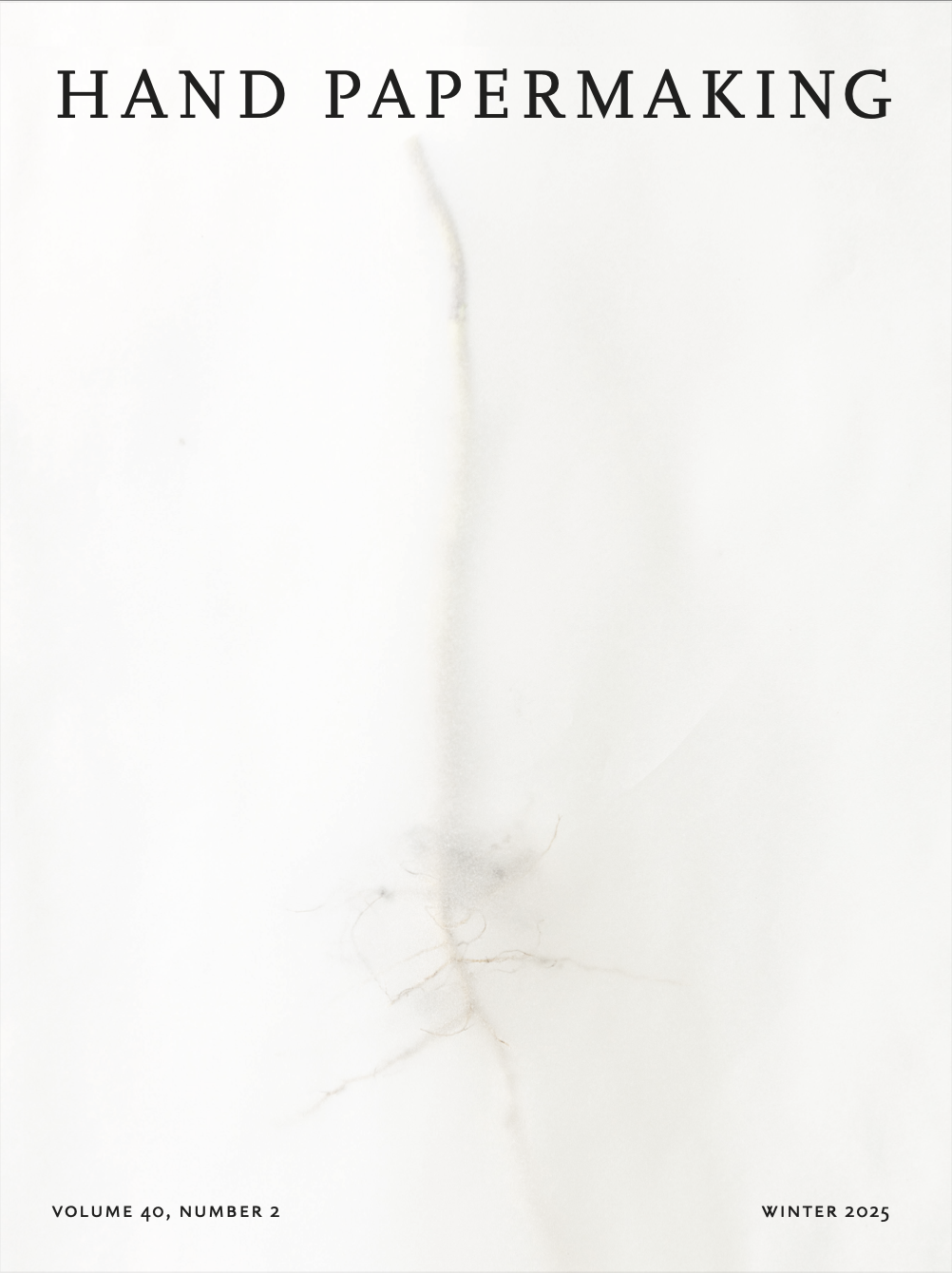

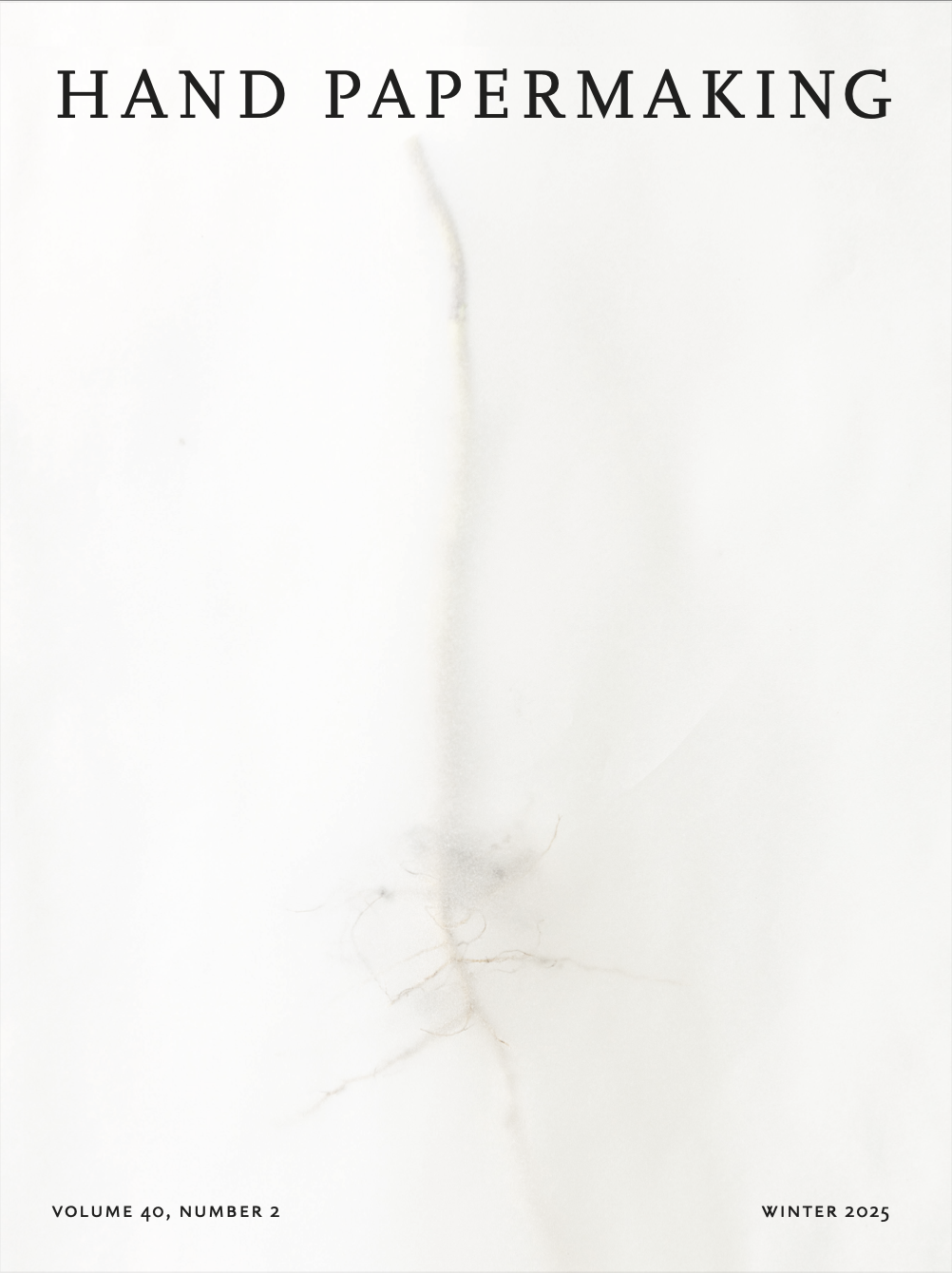

Some answers, I think, lie in these pages. As artist Dor Guez Munayer reflects in his interview with curator Rachel Winter, “paper is never neutral. It carries the weight of power, authorship, and erasure.” Thinking across paper’s status not only as a material, but as evidence in supporting official claims of belonging and ownership, Guez recognizes that “the preservation of paper—especially as a carrier of memory and history—is often a privilege” and one not always afforded to communities displaced and decimated by war, occupation, and genocide. Yet Guez resists understanding paper as a purely bureaucratic medium. He explores paper as metaphorically and physically layered, often making his artistic interventions within the strata of a single piece of paper. The paper archive is, in his hands, not a collection of facts but an accumulation of residue—both institutional and personal, oppressive and empowering, capable of wounding and healing—to be excavated and sifted. Guez captures paper’s liminal nature in his latest series, Khobiza, an image of which graces the cover of this issue. For Khobiza, he photographs Palestinian plants in the process of being pressed for preservation and posterity, a moment, he describes, before the plant “seemed to either sink into the paper or push against it.” Maintaining presence while hovering outside of and resisting paper’s conventional bureaucratic qualities, the plant forms reflect the space of Palestine and Palestinians today who exist despite being denied an internationally recognized nation-state. As he recounts, the artwork “doesn’t perform beauty…it documents something else entirely: survival in the face of annihilation.”

Palestinian dress historian and embroiderer Wafa Ghnaim also explores paper’s many facets for Palestinians: as a colonizer’s tool, as a space of preservation, and as a place of loss. Ghnaim understands the proliferation of pattern books teaching the traditional Palestinian art of tatreez, or embroidery, as a necessary intervention to preserve the practice among Palestinians in exile, longing to connect with their ancestral villages and cultural identities in the face of dispossession. Yet rather than hew to an understanding of paper-based preservation as a neutral or even heroic practice, she deeply engages with the violence paper does to indigenous, oral methodologies in preserving cultural traditions. In elucidating the ways in which the codification of patterns onto paper has limited the dynamism of this subjective, interpretive tradition, Ghnaim’s piece exposes a certain pain that emerges when a community is compelled to commit their traditions to paper. The act itself bares the losses suffered under oppression.

And it’s the pain that paper can contain which papermaker Clara Reynen explores in her essay and project, The Identified Death Toll of Palestinians in Gaza, One Year Later (2024–ongoing), samples of which are tipped into this issue. Turning to papermaking as a way to process the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza since October 2023, Reynen describes how the project began as “an act of defiance” and as a way “to make the genocide of Palestinians as unavoidable a fact as possible” on the University of Iowa campus where she made and exhibited colossal sheets of handmade paper displaying a tally of those murdered in Gaza. As a tally, the project appears at first glance to be using paper bureaucratically as a record-keeping device, working on overly large sheets to speak loudly of the horrors of the past several years. However, in the labor- and time-intensive process of making the sheets, Reynen’s own grief—but more importantly the painful losses of those lives, the number of which has increased by more than 20,000 in the mere months since the completion of her project—is poured into the pulp. While making the sheets outside and at community events, Reynen sparked dialogue with others not only about the current genocide but about the warmth, joy, and resilience of Palestinians—people like her close high school friend “who gestures wildly with her hands when she talks,” and her friend’s mother who “made us hot food and cold smoothies for long study sessions and group projects.” Presenting these beautifully mundane memories alongside the staggering death toll, Reynen reminds us of the light that existed in each of these lives, urging us never to be numb to numbers.

For many of the contributors, working on this issue lifted an otherwise heavy, dark time. Paper is normally thought of as a “light” material and it was comforting to approach the topic of Palestine from the medium of paper instead of from the latest headlines. It reminded us, for instance, of the joy produced in Gaza more than a decade ago when Palestinian children there fought to claim the Guinness World Record for the most kites flown simultaneously. Reflecting on his documentary film, Flying Paper (2013), which followed children in the Jabaliya refugee camp during this period, filmmaker and media scholar Nitin Sawhney thinks about how found and recycled paper products, like newspaper, became tools for children to assert “a right to play.” Within the context of the Israeli occupation and siege on Gaza, a light-hearted pastime like flying paper kites transforms into an act of “creative agency, self-expression, and resistance.” The efforts by Gaza’s children inspired the Kites in Solidarity movement, co-founded by contributor Melissa Bolivar, to stage kite-flying events globally in solidarity with Gaza over the past several years. Paper, Sawhney and Bolivar remind us, can be—and, perhaps, should be—child’s play.

Yet in looking to the sky to think about paper, the issue would be remiss in focusing on only the colorful exuberance of kites. Art historian Alessandra Amin’s contribution to this issue responds to the many images of paper afloat in Gaza’s skies, which have haunted news and social media feeds ever since Hamas fighters used paragliders to sail over Israel’s barrier wall on October 7, 2023 and carry out mass violence and kidnappings. Since the infamous attacks, the Israeli military has clouded Gaza’s skies not only with bombs, teargas, and armed drones, but also with antagonizing leaflets dropped from the bellies of airplanes. Gaza’s paper has gone up in smoke as the military burns universities, libraries, and schools, while Israel’s punishing blockade deprives Gazans of essential paper products like toilet paper and sanitary napkins. In surveying Gaza’s recent “paperscape,” Amin tells us something about how our common belief in paper’s neutrality can mediate our response to atrocity in such times as these.

In that vein, cultural anthropologist Thayer Hastings’ contribution about the circulation of single-page political leaflets (bayanat) to organize the mass popular uprisings of the First Intifada (1987–1993) uses a historical lens to emphasize the dangers of paper within the Palestinian context. Being found in possession of even one leaflet during the Intifada could lead to imprisonment; to evade persecution, bayanat were therefore memorized and shared orally—dematerialized from paper into oral form. Bayanat became “extra-ephemeral,” Hastings argues, as “incriminating documents that should be concealed or destroyed.” However, as Hastings’ most recent research into unconventional archives discloses, the reverse could also be true: prisoners during the First Intifada “recorded the bayanat that were read aloud over the radio at dictation pace into prison notebooks” for safekeeping and circulation. Touching on an important organizing theme of this issue, Hastings’ essay, like Amin’s, Ghnaim’s, and Guez’s contributions, crystallizes how paper’s materiality might look quite different when explored through the context of historic and current Palestinian struggle.

We close with a wide-ranging, candid conversation between artists Jumana Emil Abboud and Michelle Samour, meeting for the first time for these pages. Guided by the use of water as a touchstone across both their practices, the conversation flows from childhood memories to questions of embodiment and the power of collaborative storytelling in creating new histories. They land on a discussion about how paper’s actual porosity and vitality, despite appearing as “a fixed substrate,” might be a useful lens through which to rethink Palestine as a static entity or its current political condition as intractable. As Abboud concludes, “Palestine isn’t just one thing, right? That’s perhaps where certain parts of history have failed us, in wanting to fix Palestine into a settler-colonialists’ dominant narrative. The way I see our work is that it’s about the multitude that Palestine is.”

When Hand Papermaking’s editor approached me with the idea to devote an issue to Palestine, following on the organization’s welcome statement of solidarity, it came as a challenge. Palestine’s history with handmade paper is slim. Moreover, when I reached out to colleagues in my artistic networks, we uncovered few Palestinian artists who make or work with handmade paper. However, it is paper’s vast potential that has inspired the contributions to this issue. The essays within provide an array of tools for how to think about “the multitude that Palestine is” through the lens of paper and challenge us all to consider what paper means to and for Palestinians.

Nisa Ari

___________

NOTES

1. Gallery Anadiel Archival Papers, Jerusalem.

2. “Hand Papermaking Statement on Equity in Response to the Palestinian Crisis,” Hand Papermaking, October 16, 2024, https://www

.handpapermaking.org/post/hand-papermaking-statement-on-equity-in-

response-to-the-palestinian-crisis-2.

3. Research on the historical papermaking industries in Palestine has been guided by Israeli scholars’ interest in the circulation of ancient Jewish texts in the region, while scholarship on the use of paper by Arab Palestinians, to my knowledge, has not been extensively pursued. For English-language sources on the topic, see: Zohar Amar, “The History of the Paper Industry in Al-Sham in the Middle Ages,” in Towns and Material Culture in the Medieval Middle East, ed. Yaacov Lev (Brill, 2002), 119-33; and Zohar Amar, Azriel Gorski, and Izhar Neumann, “The Paper and Textile Industry in the Land of Israel and Its Raw Materials in Light of an Analysis of the Cairo Genizah Documents,” in “From a Sacred Source”: Genizah Studies in Honour of Stefan C. Reif, eds. Ben Outhwaite and Siam Bhayro (Brill, 2010), 25–42.