Canada’s foremost creative artist in hand papermaking, professor emeritus, researcher, agriculturist, poet, lover of life’s good things, laughter, food, music and above all the planet—Helmut Becker—departed this world on September 24, 2024, in London, Ontario, at the age of 93. Becker was known particularly for his lifelong, dedicated research and works of art with flax and hemp.

Helmut Becker was born February 24, 1931, in an area of Canada commonly referred to as the Alberta Badlands and grew up in post-depression rural Saskatchewan. Among his major influences, Becker credits Saskatchewan artist Wynona Lancaster, his first art teacher, as someone who instilled in him the drive to be a Canadian artist and art teacher. Lancaster impressed Becker with her strong conviction that art is a language and not just a skill or stunt to put down. It comes from the heart.

Other early influences include art educators Kenneth Lochhead and Arthur McKay whom Becker met as a high school teacher in Regina. Lochhead and McKay shared the philosophy that art be a direct experience and developed over a period of time. The work should then become instilled like osmosis as a part of you.

Becker studied art and art history at the University of Saskatchewan and at the University of Wisconsin. He began his academic career at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and at the University of Calgary, but made his mark as professor emeritus of printmaking, papermaking, and research at the University of Western Ontario. There Becker inspired generations of students for over twenty-five years passionately emphasizing both the creative process and technical aspects of each area.1

Becker’s former student Heather Midori Yamada recalls: “An innovator and pioneer, Helmut introduced safety standards and equipment in our studios that would be the envy now of any studio; eye washstand, giant exhaust systems, rubber aprons, filtering face masks to name a few. A recipient of a Canada Council grant, Helmut designed and engineered a hydraulic press bed which could accommodate plates, stones and woodcut planks up to six feet in length. Shining steel paper beaters for processing cotton pulp for handmade paper told of Helmut’s position as an early leader in the handmade paper world. Growing flax and making ink by grinding pigments were a few of the experiences we had as students. We had in our midst a rare kind of professor who lived and loved what he taught.”2

Becker’s creative works of art are vast and varied. He said, “I believe an artist should be free to express him or herself in any of the fine art forms of expression or combinations of these. Write a poem. Write a piece of music. Draw an image or an idea. This freedom extends to what media you wish to employ.”3

Becker’s early woodcut prints employ not only fresh and vigorous use of line and colour but also three dimensions. It was Becker’s search for a strong responsive paper capable of retaining the deep embossing required for his woodcut prints that led him to hand papermaking and a pivotal meeting in 1969 with Douglas Howell at his studio in Oyster Bay, New York. Howell worked with raw bast fibres of hemp and flax using minimal or no chemicals to process the fibre in a Hollander beater he had built and designed himself. Becker could see that the resulting paper had beauty and character with superior quality and strength not found in commercially made paper available to artists at that time. He realized then to be fully in command of the artistic process he would need to grow his own flax and build his own processing machinery, including a stainless-steel Hollander beater and hydraulic press; all of which he subsequently did while producing artwork of equal depth and importance.

Becker started growing fiber flax in 1976 on Bev Katzin and Ron Walker’s farm near Blyth, Ontario where years ago fiber flax was grown and exported to Ireland for linen production. He subsequently began growing on a larger scale with William Cooke on his farm near Stratford, Ontario and then with Peter Duenk, Field Station Manager at the University of Western Ontario’s Environment Sciences Field Station in 1977; a relationship that was to span four decades. Duenk recalls, “I planted and grew it, but it was Helmut who would be the one to spend hours and days in the field station plots. Under the hot summer sun, he would harvest and process the plant material to then use it for his paper.4

Much of Becker’s inspiration for working with hemp, which he began growing at the UWO Field Station in 1995, is drawn from his interest in the early practices originating in ancient China. Retrieving the hemp fiber after retting and drying to release the long, strong, white bast hemp fibers from the woody centre took Becker about three hours for each kilogram. Becker believed this slow work was required to bring the brain from intellect to instinct. It was through this meditative process that he said his creative ideas emerged.5

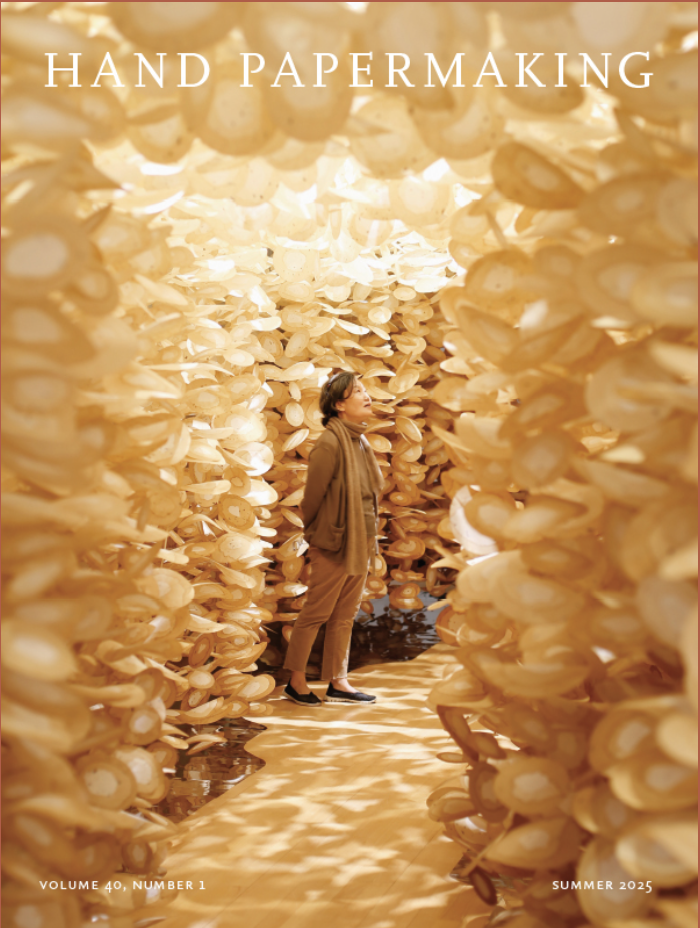

In 1999 Becker was involved in the creation of a multimedia installation at Play Factory Paper, a unique hand-papermaking festival in Hui Lan, Taiwan. In this work we see Becker stretching the creative realm of hand papermaking and his own practice by employing not only hand papermaking but also recorded sound, found natural objects, and living plants. The bittersweet irony of this event was that the entire installation was destroyed by a typhoon hours after its completion. Amanda Degener recalls the profound disappointment of the event organizers and that Becker “saved the day” when he stood up and made a speech addressing the significance of the creation of the installation despite its destruction noting the ephemeral nature of our existence. Degener adds that “Helmut confidently took the microphone and convinced all that something great had happened. He cited the international exchanges between people, the process of making work together, and he even welcomed the typhoon’s participation.”6

Becker’s most recent work is exciting as it includes not only the use of hand-grown and hand-processed fibres but also computer-generated images, sound, and music. He felt free to express himself in a multitude of genres in combination with technology. Evident in all of Becker’s work is his concern for the ecological future of the planet and humanity. Becker believed that “Art without humanity or without feeling is dead.”7

Helmut Becker, a creative force who loved to share knowledge will be remembered as a remarkable artist and inspiration, an original soul. In a 1999 interview with Amanda Degener, Becker said he thought if he came back into this world he might come back as a flax plant. He said, “The more I work with the fiber flax plant the more it is alive—like other things, like earth, water, and sun.”8

___________

notes

1. See “Remembering Helmut Becker,” Department of Visual Arts, University of Western Ontario, https://uwo.ca/visarts/news/2024/11-RememberingHelmutBecker.html

(accessed February 14, 2025).

2. Heather Midori Yamada, e-mail message to Jennifer O’Connor, September 2025.

3. Helen O’Connor, “Helmut Becker, Profile,” Book Arts arts du livre Canada vol. 7, no. 1 (2016).

4. Peter Duenk, e-mail message to the author, February 17, 2025.

5. Helmut Becker, “Growing and Hand Processing Fibre Flax and Hemp for Hand Papermaking,” paper presented at the 2008 International Conference on Flax and Other

Bast Plants (Fiber Foundations—Transportation, Clothing & Shelter in the Bioeconomy), Saskatoon, SK, Canada, July 21–23, 2008, https://www.academia.edu/7064900/Growing_and_Hand_Processing_Fibre_Flax_and_Hemp_for_Hand_Papermaking_Helmut_Becker (accessed February 2025).

6. Amanda Degener, e-mail message to Jennifer O’Connor, September 2025.

7. Helen O’Connor, “Helmut Becker, Profile,” Book Arts arts du livre Canada vol. 7, no. 1 (2016).

8. Amanda Degener, e-mail message to Jennifer O’Connor, September 2025.