Site-specific installation excites me, but it also scares me. Maybe it is exciting because it scares me? The openness and constraint that accompany a direct response to existing spaces appeal to the problem-solving side of my brain, while the experience of responding to variables and shifting circumstances is creatively stimulating. I have come to understand that this balance requires me to stay open and allow outside elements to impact the work. This does not mean however, that I do not prepare.

For an exhibition, a large part of what I do is the installation prep—an array of spreadsheets listing order of operations and color-coded numerical systems designed to ensure that a labored-over system disappears into an experience that feels effortless. My goal is to create work that is experiential, something that transports the viewer. Nothing ruins an encounter more quickly than clunky hardware and clumsy planning. Preparation is my game. The better prepared I am, the better I can manage the inevitable unplanned occurrences. To plan for site-specific installations, which cannot truly exist in any location except for in the space they are intended for, I build scale models, sample materials, test lighting, and shift around variables.

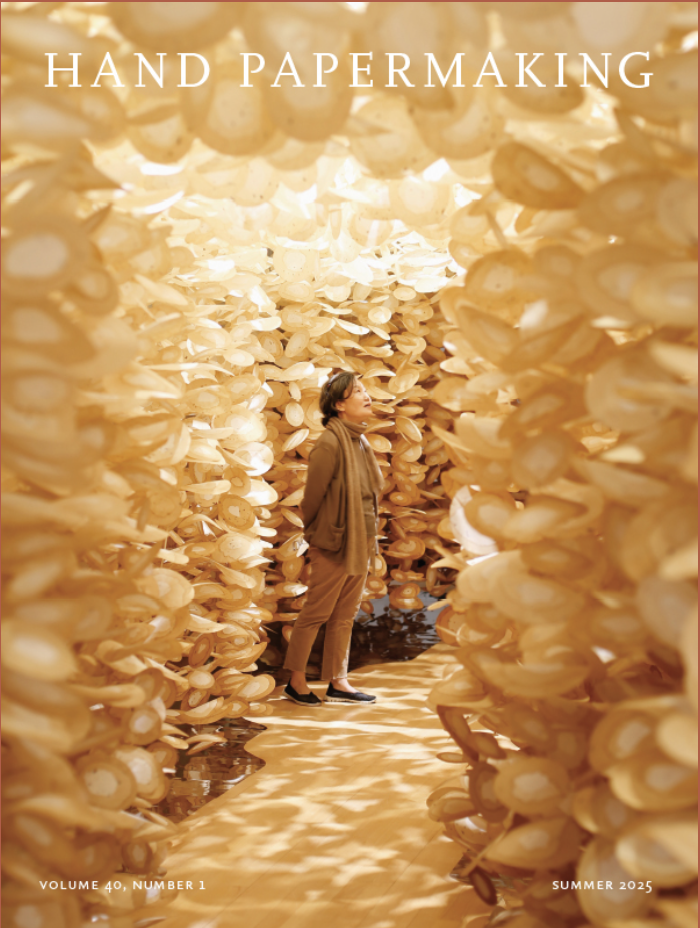

In the spring of 2022, I was invited to create a site-specific installation at the Tarble Art Center. The work Falling Into Milk1 would challenge my approach, pushing me to respond in new and vulnerable ways.

The installation site was composed of a 60-foot-wide serpentine span of floor-to-ceiling windows treated with a frosted vinyl, a polished concrete floor, and a central skylight. On the opposite side of the room, were multiple doors and windows. The many light sources impacting the space made it challenging to fully understand and account for. The plan was to create an installation by applying handmade paper directly to the length of windows to control how the sunlight would enter the space.I borrowed this approach from an adjacent series of works developingin my studio; one example is That Which Has Become Known (South).

act i: birth

Falling Into Milk Act I sets the stage. The composition of the positive space created by the pulp and the negative space surrounding it conjures images of continents in flux. One could be forgiven for attempting to identify the meandering shore or tree line it is directly referencing. Alternatively, one could be gazing into the past—a window into a stellar nursery from 100 million years ago. The mirror finish of the floor creates a sense of interiority—peering out from inside the depths of a cave. As light from the sun moves day into evening, porous illumination surrenders to the overall mass of the form. Confusing what is terrestrial with what is celestial against a shifting pattern of light we recognize the cycles of life and are reminded that the world is in a state of constant flux, renewal, and decay.

act iii: thought

Falling Into Milk Act III introduces stacks of books, each one individually sealed in layers of overbeaten abaca and flax then dipped in ink. The geological layers of strata are formed by books on history, philosophy, religion, poetry and everyday stories. The words collapse into an architecture built from black bricks. Time forgets authors, words, and sources of knowledge and instead presents a collection of ideas that moved a society into multiple directions.

act ii: life

Falling Into Milk Act II welcomes the arrival of new players—a hollow ovoid form dressed in gold, an island of felted wool and scattered metallic slices of earth. The blacked cavernous interior of the form can be viewed through an opening at its crown. Tangled raw wool laden with chaff mirrors the paper composition above, connecting window and ground. Metallic slices of earth appear as an inverse of the holes above—a nursery of stars fallen to earth. What were once apertures of light are now terrestrial forms—animate and burgeoning.

act iv: reclamation

Falling Into Milk Act IV builds upon the previous iterations and concludes with a final act—the addition of fallen peach tree branches. The concave branches cradle the architecture below offering the possibility of a funeral pyre while the peach tree, as a symbol of immortality and longevity, suggests that the prevailing essence of nature will thrive.

For these installations, I built a custom-made concrete textile imparted with small holes to install in a sun-facing window. The fissures and apertures in the knit structure cast dappled light onto the floor and walls. As the sun moves through the sky, I cataloged the trajectory of these illuminated patterns by tracing the moving shapes with graphite, and later gold and silver leaf, directly onto the surfaces of the room. Over the course of multiple days, the pattern grew ever more offset with the shifting tilt of the earth in relation to the sun. These time-based drawings allowed me to connect my scale with that of the cosmos and to recognize our constant state of flux. The tiny holes in the handmade paper for Falling Into Milk would slowly catalog and reveal our changing position and create an accumulating time-based drawing across the floor.

I laid the groundwork by examining as many variables as possible: I installed the frosted vinyl on my studio window to examine how using paper rather than concrete might change the outcome; I observed the sunlight coming in; I evaluated paper pulps; mixed in ink and inclusions while testing methods of application. I selected two different pulps—an overbeaten abaca and a mixture of esparto grass and sisal. The abaca offered a smooth, transparent finish while the mixture of esparto grass and sisal presented an intriguing pebbly texture reminiscent of concrete. Like previous site-specific installations, I prepared as much as possible—testing color, texture, light, application, and timing. When testing was complete, I readied the pulps (plus extra); put together a kit of extra tools—including moulds and deckles, felts, vats, Pellons, as well as a hopper sprayer—all of which I knew I would not need; collected my paint, inks, graphite, metal leaf; and hit the road to Illinois.

Upon my arrival I was met with Eastern Illinois University art students prepared to get their hands wet. We poured pulp onto pieces of Pellon, carried them over to the window and squeegeed on from the back. Care had to be taken that it would not just slide down the slick surface. A tempera medium was added so that as the water dripped down the window, its trajectory would be captured. We worked for hours. I paid careful attention to the floor and the accumulating soft shadows. It was clear early on that my plan would not work in that space; the light was not right. Although I had tested the pulp application ahead of time and at- tempted to recreate the lighting conditions, my preparation did not accurately capture the conditions of the space. My plan was no longer viable. As Winifred Lutz once said to me, “Respond to the conditions you have rather than what you had hoped to have.” In that moment I recognized the challenge; I was free of previous expectations, but with the pressure to respond in time; I would not be able to rely on my color-coded install guides. This now became a project space.

In order to respond, I looked to what inspires me. Like others across the world, I was mesmerized by images captured through the James Webb Telescope. Depicting the far reaches of our galaxy they provide a glimpse into the early days of our solar system—the birth of stars. This window into cosmic time recognizes an edge of our present knowledge. Within my work I am interested in limitations of human perspective and thresholds of awareness—an inquiry of what is out of reach. My practice of cataloging observations of light began from this interest. It started asa way to touch and begin an exchange with this expansive world we occupy. This past approach could not be applied to the project at hand. Instead of capturing and marking time, I would shift to exploring a story about time. This new proposition would be driven by narrative.

Over a series of nine months, I made four trips back to the site to develop Falling Into Milk. Although the original intention of the installation was not realized, something new emerged. An accumulating series of set dressings moved us through time from dawn to dusk—from fall to spring mapping time on a continuum. Abstract in nature, the forms invited one to consider the course of time, from the planetary to the terrestrial, to the arc of how we arrived here, where we may be headed and what agency we may have in this story.

My practice requires planning, sampling, testing, and research. I like to imagine that I have a sense of control, but when arriving on site there is always a level of unpredictability. This is not unlike how I engage with the conceptual underpinnings of my practice. I am interested in the illusion of control and how we operate within that space. There are always unforeseen conditions and what better way to navigate them than to reevaluate, readjust, and make something unexpected and new.

Author acknowledgements: Thank you Jennifer Seas, Director and Chief Curator at the Tarble Arts Center. Many thanks to EIU students: Karla, Kat, Grace, Lilly, Ellie, James, Sam, Candy, Eric, Raiven, Francis, and Mya for your assistance.

1. “The work’s title alludes to the shared Greek origin of the words galaxy and milk, offering a connection between animal bodies and planetary bodies, between terrestrial existence and our place in the cosmos,” as described in exhibition wall text by Jennifer Seas, Tarble Art Center Director and Chief Curator.