As a long-time artist, educator, and “paper investigator,” I thoroughly enjoyed serving as chief curator for the 2023–24 International Biennial of Paper Fibre Art (IBPFA).1 Valuable lessons were learned after more than a year and a half of working closely with organizers, three co-curators,2 selected artists, and an installation team.3 My perspective as both curator and working artist is shared here with hopes it will prove useful to individuals on all sides of a paper exhibition experience.

The first task as curator was conceptualizing an overarching theme, which is more difficult than one might imagine. The challenge: to be specific enough for clear interpretation by the artists while also being expansive enough to spark the interest and imagination of both artist and audience.

“EARTH SPEAK: Giving Voice to Paper” was an experiment of sorts, eliciting works from artists around the globe to see what wisdom might be emerging at this point in time, especially from paper artists who have such strong connections to their communities and the natural environment. As co-curator Dr. Jen-Kuan Yau expressed so eloquently, “[We wanted to] create an outlet for artists to re-examine historic and contemporary paper art while exploring the dialogues between human society and paper as an artistic medium.”4

After we issued the call and the applications began arriving, the next curatorial task was to develop a scoring rubric that would be used by our team for reviewing the works submitted online. While it may seem odd to use something so structured for what many consider a subjective process, past curating and teaching experiences led me to rely on this tool as an invaluable starting point. Selecting a small number of artworks from a large number of applications can be difficult (and stressful) and having a framework to keep one on track is essential.

We considered four overarching criteria: theme, concept, materiality, and quality.

theme: Does the artwork communicate a clear connection to the theme?

concept: Does the work demonstrate a strong concept and fulfill the artist’s stated intentions?

materiality: Did the artist use their material as effectively as possible?

quality: Is there a high level of craftsmanship in the work?

After averaging scores from rubrics completed by all four jurors (myself and co-curators), we organized the artwork into three tiers for final review and discussion that ultimately led to more nuanced decisions in the final stage of selections. Working with the co-curators was crucial as it provided fresh perspectives, cultural sensitivities, and wisdom from shared years of experience. As chief curator, I was expected to make the final selections and did so after carefully weighing several factors:

• General agreement among fellow juror

• Balance of mediums represented (e.g., two- and three-dimensional, artist books, installations, abstract, representational

• Compelling connections and dialogue among the artworks

• Broad representation of as many countries and cultures as possible, including Taiwan, the host country.

Participating in this type of review process was extremely informative. For starters, it was a persuasive reminder of how important it is for one’s work to be relevant to the theme of an exhibition. While it is tempting to gamble and hope the curator(s) see something relevant in one’s work, it poses a significant expenditure of time for both artist and juror. As co-curator Jan Edwards mentions in her post-exhibition review: “Artists applying for any exhibition (not just the IBPFA) must read the concept details and consider what the curator is looking for and the context.... Many interesting, well-crafted works are rejected based on lack of relevance.”5

It was also clear how important it is for one’s work to be accurately reflected in the artist statement and vice versa. Works that aligned with the artists’ stated goals rose quickly to the top.

Quality of images was also key. When tasked with reviewing hundreds of images, photos that did not meet the required resolution or were lacking in detail were much easier to dismiss. In contrast, photos properly sized with multiple perspectives and detail images reflecting subtle aspects of the work gained our attention.

Finally, during the last phase of the curatorial process, I found myself returning to one main question: Did the work give voice to the material and allow paper’s distinctive capabilities and qualities to come through?

Once final selections were made and the artists notified, it was time for them to package and ship their works, which many will tell you is their least favorite part of exhibiting in faraway places. As we worked through the process, more observations were noted for future reference. Some were unique to paper artworks and others were general best practices for any exhibiting artist.

When it comes to shipping paper works, the good news is that the medium is (usually) lightweight compared to other traditional media. The flip side is that it can be easily damaged if not strategically packed. Like the curator wading through hundreds of applications and images, think of the person working long hours in a shipping facility and handling thousands of packages a day. Artwork packed with care, preferably one box nested inside of another with plenty of padding, will fare much better.

Working closely with executive organizers Bod Design (Taipei) and SPACEWOOD Design (Nantou) was invaluable. It was a great learning opportunity to witness SPACEWOOD staff painstakingly unpacking and photo-documenting every work as it arrived in Taiwan and then sending images and notes to both curator and artists. From an artist’s perspective, it underscored the importance of being diligent about completing requested paperwork and responding to communications with the installation team in a timely manner. From the installation team’s perspective, those artists who took the time to provide as much information as possible, including any special handling considerations, were greatly appreciated. As curator, I was impressed and grateful for the care everyone put toward these endeavors.

This process also provided a potent reminder to pay close attention to size limitations of the various international shipping couriers, as exceeding those dimensions can involve outrageously expensive freight charges. Larger works should be designed to be modular, allowing for easy packing and reassembly. A major takeaway: whenever possible, considerations for packing, shipping, and exhibiting abroad should happen during the art making process and not at the end.

A stellar example of this type of careful planning and forethought was the expansive multi-media installation Once She Dries, a collaboration led by US artists Nancy Cohen and Meagan Woods6 that involved long swaths of paper stretched across large open spaces. When discussing installation options, Woods, who uses sewing in her art practice, suggested stitching a hem along the paper to run wire through, providing additional support.7 As Cohen shared later, “This elegant solution allowed more options while also lending the work delicacy and malleability, perfect for the installation as well as for shipping.... Loops on the ends of each paper ribbon provided additional flexibility.”8

Gloria Florez, a Colombian-born artist who now lives in Australia, described her strategy, “One of the biggest challenges I’ve faced is how to transport, install, and store my work.... Moving away from works restricted by frames allowed me to transition from creating single artworks to exploring the realm of installations. This has been a liberating way to create, as it feels like there are no rules—only possibilities. When it comes to packing, storing, and transporting, this approach has allowed me to create multiple pieces that can be folded into small bundles or rolled together into one.”9

Beyond packing and shipping, paper’s sensitivity to temperature and humidity is another important consideration that is unique to the medium and often something we do not think about as we are used to seeing our work in its native habitat, so to speak. I first became aware of this when transporting and exhibiting my own paper pieces, noticing dramatic changes as they were moved from one location to another.

As it turns out, paper needs time to acclimate and is most stable in cool, dry environments. While we cannot always control this, it is something to be aware of when exhibiting work. In recent years I adopted the practice of including instructions with my artwork to ask recipients to unwrap and let it adjust for a day or so before installing and I noticed that several artists for this exhibition did the same. Lately, I have been researching the feasibility of including desiccant papers with shipped works or even incorporating them into framed and/or installed works. (Any insights from fellow paper artists are welcome.)

As valuable as these administrative and logistical observations have been, by far the greatest reward of serving in this capacity was the opportunity to get to know kindred spirits from countries and cultures around the world. The level of professionalism of the 44 selected artists was inspiring.

As we discussed their work and logistics for the exhibition through countless emails or, in some cases, Zoom meetings, common traits showed through—strong communication skills, the ability to plan to the smallest detail, and incredible flexibility. In every instance, the artists took changes in stride and worked closely with the administration to produce a beautiful and compelling exhibition in two separate exhibition spaces: the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei (November 2–14, 2023) and the NTCRI Craft Design Hall in Caotun Township in Nantou County (December 8–March 31, 2024).

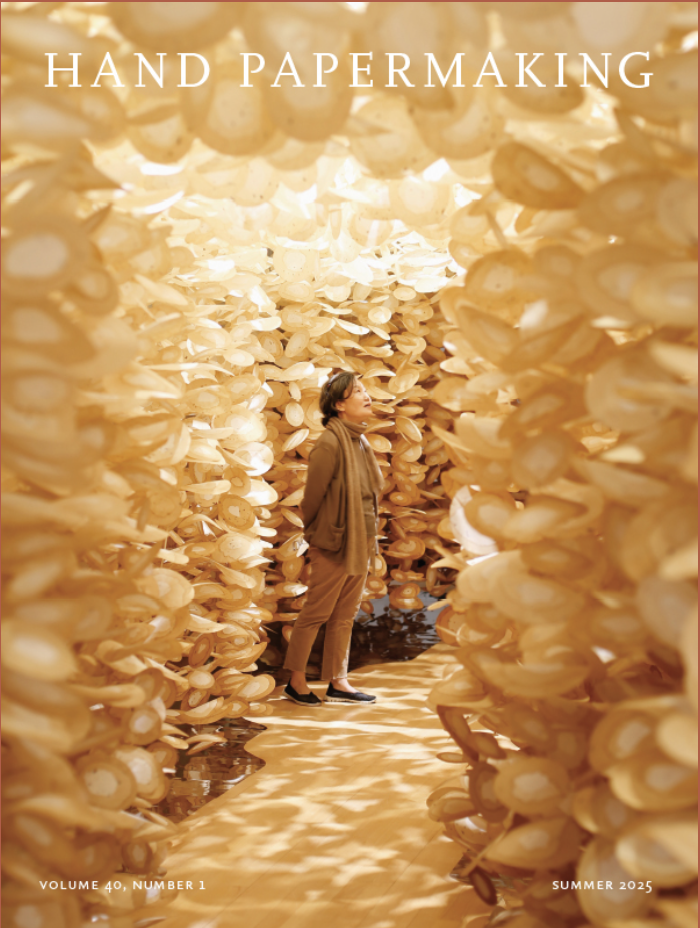

Veteran exhibitor Yoo Jounghye (South Korea) provided an exceptional example for us all. Supplying multiple diagrams of her stunning installation The Path Where Moonlight Flows (originally 12 x 4 meters) with every detail thought through, she graciously adapted her installation and schemata as the team worked to find the appropriate space.

US artist Elizabeth Mackie, with her work Delaware River, learned late in the process that her large-format paper exceeded the courier’s maximum size. Without hesitation she adeptly produced and shipped another sheet for her multi-media installation.

Perhaps the most flexible was Gloria Florez who shared her philosophy in our post-exhibition discussion about her work Forest Ambassadors: “Transforming a concept into a tangible artwork is a long journey, often diverging from the initial vision. Materials or techniques may not behave as expected, requiring creative problem-solving and adjustments...whether working on a residency, creating an artwork, collaborating or installing artworks, adaptability is paramount.... Installing artwork in a new space brings a mix of anticipation and excitement, along with various challenges. Each gallery presents unique spatial and logistical limitations that demand on-the-spot problem-solving and adaptability. Working within tight time constraints, such as completing the installation in just three days, intensifies the emotional journey of the process. However, despite these hurdles, the experience is profoundly invigorating.”10

Nancy Cohen echoed similar sentiments: “There is nothing more exciting than coming to a new space and collaborating with others.... Helping each other, troubleshooting together; seeing someone else’s project develop while you are working on yours; answering a question; sharing an idea, etc.; that is a special thing.”11

For artists thinking about applying to future international paper exhibitions, I would like to provide one last bit of encouragement courtesy of Aleksandra Pulińska (Poland) who courageously combined her paper work with performance art for the first time: “Participation in the Biennial was very developing. It was great to interact with the other invited artists and the curatorial team. I feel the intensity of those ten days in Taiwan engraved a lasting impression. It was amazing to experience that, although we represented different continents, aesthetic values and issues of perception in art are beyond culture and are universal....Experiencing the tradition and culture of handmade paper production in Taiwan was invaluable.”12

The author would like to acknowledge the entire IBPFA Team for their exceptional efforts including the organizers The National Taiwan Craft Research and Development Institute and the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall; co-curators Jan Fairbairn Edwards, Dr. Jen-Kuan Yau, and Wei-Lin Yang; exhibition planners Dr. Jen-Kuan Yau and Tii-Jyh Tsay; executive editor Ching-Fen Hsiao; project coordinator Ye Yang; and executive organizers SPACEWOOD Design(Nantou) and Bod Design (Taipei). 非常感谢你 (fēi cháng gǎn xiè nǐ; thank you very much)!

___________

notes

1. A brief history: Originally orchestrated by the Association Chaîne de Papier in France after the successful paper exhibition “L’Avenir en Papier” (2010), its founder Jan Fairbairn Edwards expanded the scope of the biennial to an international stage by partnering with the National Taiwan Craft Research and Development Institute (NTCRI), which has served as major sponsor and host since 2018. In 2023–24, the NTCRI carried the IBPFA into a new phase as Edwards stepped away to pursue new artistic goals.

2. IBPFA founder Jan Fairbairn Edwards, and Dr. Jen-Kuan Yau and Wei-Lin Yang from the NTCRI.

3. Working under Edwards’ tutelage as a co-curator for the 2021–22 Biennial (“Kozo Contemporary”), I was pleased to accept the offer to serve as chief curator for the 2023–24 event hosted in two locations in Taiwan, beginning with a two-week exhibition at the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei with Bod Design serving as executive organizers of the exhibition followed by a second four-month showing at the NTCRI Design Hall in the Caotun Township of Nantou County with SPACEWOOD Design Group serving as executive organizers.

4. Dr. Jen-Kuan Yau, Manifest of IBPFA (via email), October 22, 2022.

5. Jan Fairbairn Edwards, post-exhibition review in email correspondence, June 9, 2024.

6. Once She Dried collaborators include: Nancy Cohen (US), art installation; Kourosh Ghamsari-Esfahani (Iran/US), violin and sound; Casper Leerink (Netherlands/Canada), piano and sound engineering; Xinyue Liu 劉新悅 (China/UK), video projections; Amanda Sum (Canada), vocals; Meagan Woods (US), story.

7. A fascinating TED talk by Meagan Woods about stitching in reverse can be viewed here: https://www.ted.com/talks/meagan_woods_stitching_a_new_form_of_progress_lessons_from_sewing_about_making_and_moving_in_reverse (accessed November 19, 2024).

8. Nancy Cohen and Meagan Woods, post-exhibition discussion via Zoom, February 26, 2024.

9. Gloria Florez, e-mail correspondence with the author, June 2, 2024.

10. Ibid.

11. Nancy Cohen and Meagan Woods, post-exhibition discussion via Zoom, February 26, 2024.

12. Aleksandra Pulińska, email correspondence with the author, June 22, 2024